The Gothamite is supported by 1 reader like you. (Thanks Mom and Dad!)

If you’d like to help me pay off my credit card debt, smash that subscribe button below and choose one of the top 3 subscription plans.

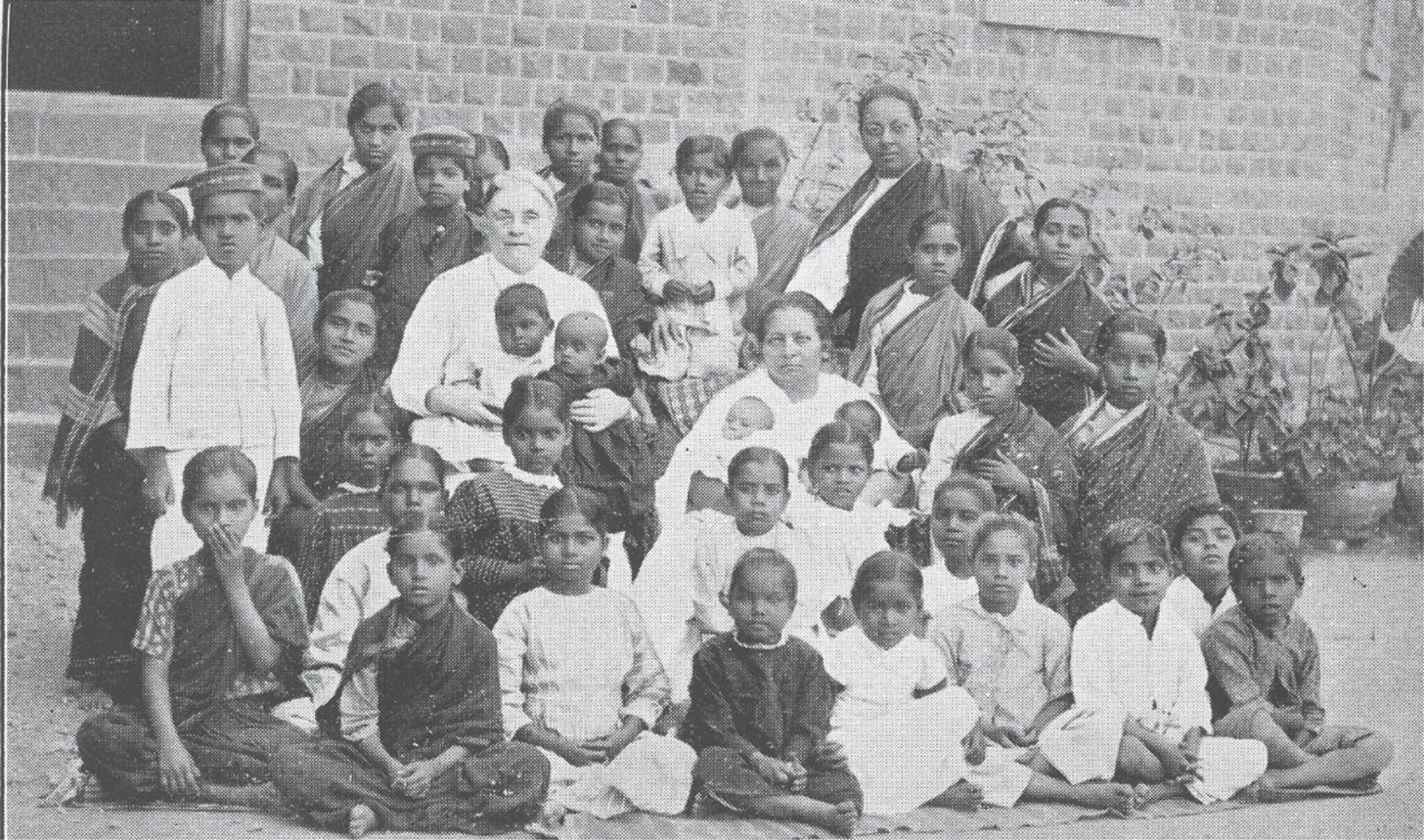

Disclosure: I have a family member who was raised in Pandita Ramabai’s Mukti Mission.

Don’t let the commemorative stamp fool you. Pandita Ramabai had a lot of haters in her time. She was born Rama Dongre in 1858 to a high-caste Brahmin family. Her father, a radical feminist named Anant Shastri Donagre, was forced to flee his family home because he taught both his wife and daughters to read.

Rama lost her parents and older sister, Krishna, when she was 16. She and her brother Shrinivas moved to Calcutta where they made a living reciting Sanskrit scripture. It was there that her mastery of the Hindu texts earned her a title no woman had been given before: “Pandita,” which means scholar. The suffix -bai was added to her first name as a sign of respect. So Pandita Ramabai means roughly translates to “Madam Professor Rama.”

But she didn’t let titles make her complacent. This Pandita was a social justice warrior, advocating for the emancipation of women. And when her brother died, she broke the rules again by marrying her brother’s friend Bepin, a man below her caste.

Just two years later, Pandita Ramabai was a single mother. Bepin left her with no living family except for her daughter Manorama, whose name means beautiful. The Pandita had now lost her entire immediate family and her husband. She was 23 years old.

She went to England with little Manorama in tow in order to study medicine. That’s when the controversy really started.

Ramabai converted to Christianity and took the name Mary, infuriating her supporters back home. She also angered the Church of England by refusing to give in to their cultural imperialism: she kept up a vegetarian diet and refused to dress like an Englishwoman. She believed that Christianity was compatible with her Indian heritage, that it didn’t erase her culture or Westernize her.

From England, she went further west, to America where she attended the graduation of the first-ever female Indian doctor, Anandi Dopal Joshia, herself a figure of controversy. Ramabai met up with other high-powered women’s rights advocates including Harriet Tubman and Frances Willard. She identified with the plight of African Americans and Native Americans.

She moved back to India to continue doing social work. Her countrymen were not pleased. She was accused of “trying to set afire the ancient religion of her compatriots with the help of foreigners.”

When Manorama died at the age of 40, Ramabai didn’t last much longer. She died at 63, having been marginalized during her life and ignored by mainstream history. It was the price she paid for her Christian faith and critique of religion-backed patriarchy.

“A life totally committed to God, has nothing to fear, nothing to lose and nothing to regret.”