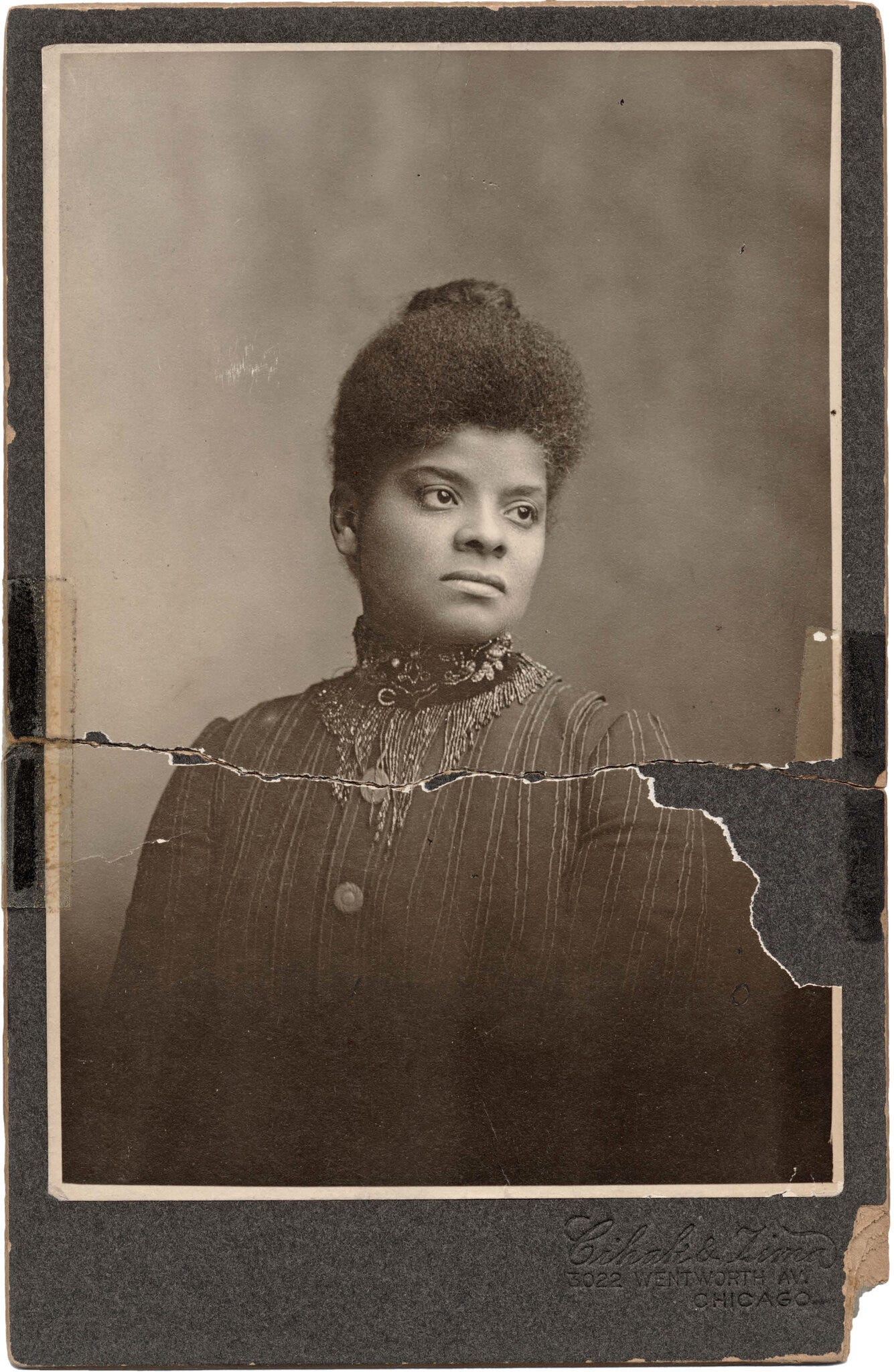

Ida B. Wells Took a Bite Out of Racism

Literally.

70 years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat, Wells got herself thrown out of a railroad car for the same “offense.” Only she managed to to chomp down on one of the racists who manhandled her.

It was September of 1883 and the 21-year-old Wells was a school teacher who took summer classes at a nearby HBCU. And she didn’t let the railcar incident slide. In an era when women couldn’t vote, she sued the railroad. And when big rail paid off her African-American lawyer, she just hired a white attorney.

Sadly, she lost the lawsuit in the end, writing this in her diary:

I felt so disappointed because I had hoped such great things from my suit for my people … O God, is there no redress, no peace, no justice in this land for us?

Ida Might Not Have Liked You

She stood under five feet tall, but was known to rip into anyone, even friends or allies, if they weren’t committed enough to her causes. “She didn’t suffer fools and she saw fools everywhere,” her grandson Troy Duster told The New York Times. Her scrappy attitude meant she had a hard time maintaining close relationships.

Of course, The Times once called Wells “a slanderous and nasty-minded Mulatress,” so keep that in mind.

When she wasn’t busy teaching or suing, Wells was writing news articles and editorials. One of her early topics was her treatment on a certain railway car. But it was her article about the bad conditions of Black schools that got her fired from her teaching job in 1891.

Undeterred, she doubled down on journalism. Her next topic?

Lynching

is defined by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People as “the public killing of an individual who has not received any due process … that white people used to terrorize and control Black people in the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly in the South.”

All the way from 1882 until 1968, there were over 4,700 lynchings in the United States, according to the NAACP. (Wells helped found the NAACP, by the way, though her name was left off the official list.)

In 1892, just a year after getting fired from her teaching job, Wells saw three of her friends get lynched by a white mob in Memphis. Here’s what she wrote in response:

There is, therefore, only one thing left to do; save our money and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons.

Ida B. Wells, Free Speech and Headlight

Then Wells, just 30 years old, began an investigation that would cement her place as one of the best to ever do it. She traveled the South for months, interviewing eyewitnesses and digging up dozens of records on lynchings.

Calling Out Racists Can Be Hazardous to Your Health

Luckily Wells was in New York City when a white mob ransacked and destroyed the newspaper where she worked. They had gotten all riled up by her editorials opposing the lynching of black folk. Maybe it was because she said:

Nobody in this section of the country believes the threadbare old lie that Negro men rape white women.

or when she added:

If Southern men are not careful, a conclusion might be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.

Her take-no-prisoners editorial earned her this response from The Daily Commercial, a newspaper that is still around today:

The fact that a Black scoundrel [Ida B. Wells] is allowed to live … is a volume of evidence as to the wonderful patience of Southern whites. But we've had enough of it.

The Daily Commercial, May 25, 1892

Just four months into her New York exile, Wells was ready to publish what she had learned about lynching in a pamphlet called: “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.” Three years later in 1895, she published “The Red Record,” 100 pages of statistics and accounts of lynching cases.

Her conclusion?

A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home.

If you’d like to read more about Ida B. Wells, here are the sources I used to write this post: